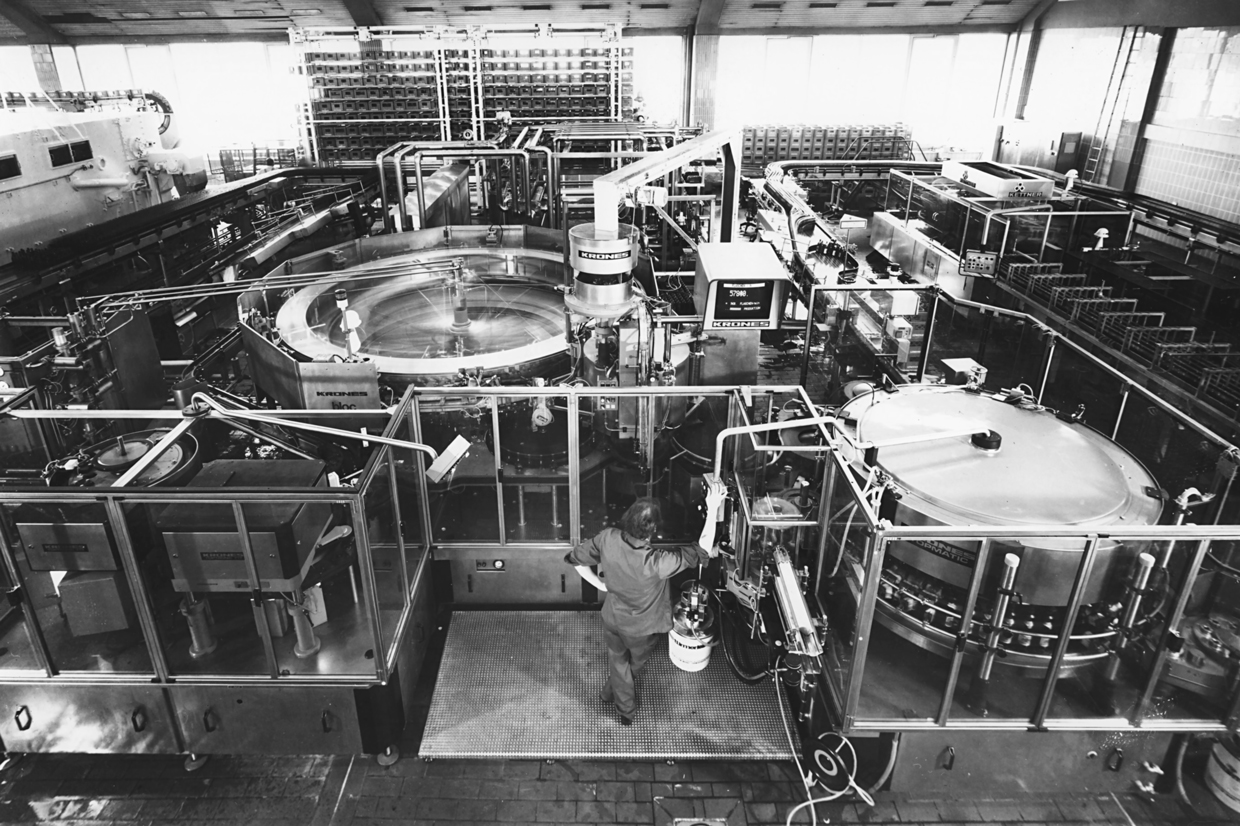

In 1975, Hermann Kronseder tackled an idea he had been pondering for some time: mechanically interlinked machines, preferably without free container movement on conveyor belts. A single block, in which starwheels or feed screws pass bottles individually from one machine to the next. It was a revolutionary concept in the beverage machinery sector because, back then, nearly all of the machines in a filling line were set up at considerable distances from each other. Only the filler and the closer formed a single unit at the time. The machines were connected by way of long stretches of conveyor belts, with accumulation tables preventing stoppages from affecting the entire line. A certain minimum level of such buffering was needed in order to ensure a line’s efficiency. Or rather, that was the conventional thinking at the time.

But Hermann Kronseder wanted to do away with as many accumulation areas as possible. In Europe in the 1970s, beverages were filled almost exclusively into glass bottles. When these bottles run up against each other on the accumulation table, they generate a lot of noise. And bottles are liable to burst, fall over or jam under the pressure of backed up bottles, which in turn results in downtimes. Hermann Kronseder figured that around 80 per cent of all issues and downtimes impacting a line’s efficiency could be attributed to too-generously dimensioned accumulation areas. He added to the calculation the conveyors’ enormous requirements for space, operating personnel and energy as well as the initial cost. He was convinced that there had to be a more elegant solution. He thought, “If a machine is repeatedly having the same error, I don’t need to build a longer accumulation area. What I need is to analyse and fix the cause of the error at the design level.” His logic went as follows: Once we’ve managed to get the machine to run virtually without errors, then we can synchronise it with other machines in a block, with no accumulation areas needed.